Messaging Recommendations

Audience: Teachers

The following messaging recommendations are informed by insights and findings from The Math Narrative Project. They provide guidance on how to effectively communicate with 6th to 10th grade students, parents*, and math teachers. Recommendations include guidance about specific framing, language, and stories that research participants found persuasive. They also provide insight into what types of messengers are best positioned and most effective in delivering a particular message.

The recommendations on this page are intended for people communicating directly with teachers. They are meant to support professionals, including teachers, instructional designers, district leaders, curriculum developers, content developers, and others who work to engage, motivate, and enable students to learn math.

*Throughout this website, the research team uses ‘parent’ to refer to both parents and guardians.

Recommendation #1

ELEVATE STUDENT AGENCY: Messaging should elevate student agency and center students’ emotions and experiences, which are critical to their math learning.

Why is this important? Teachers are often trained to see their role in the classroom as delivering information to students and students’ role as absorbing information. This one-way relationship can constrain students’ learning and undermine students’ agency in learning math.

IN TEACHERS’ OWN WORDS:

I think it’s helpful to hear from students in such an honest situation like that. There’s a lot of times, because of the pacing and the things that are going on, that we don’t get to have those nice one-on-one conversations for them to really open up like that, so I liked hearing their point of view.

White Female, Teacher, Texas

Source: MNP Teacher Survey Data, n820 respondents

Encourage teachers to be curious and empathize with students’ emotions and experiences learning math, in part by positioning students as critical messengers.

You can:

- Share a range of first-person student stories that give teachers insight into students’ emotional experiences learning math.

- Show teachers the barriers that discourage some students from seeking help and the impact teacher behavior has on students’ learning environment.

- Create opportunities for teachers to hear from young people (who are not their own students) about their math classroom experiences to foster empathy and understanding.

- At the beginning, the student talks about their desire to “get” the concepts they are being taught — it is why they are asking questions.

- Detailing the student’s motivation to ask questions — and also the fact they are nervous about it — helps some teachers reevaluate how their actions in the classroom may create barriers to students asking for help.

I will try to spend more time thinking like a student as to why they are not working or feel afraid to ask questions.

Black Female, Teacher, Texas

Source: MNP Teacher Survey Data, n820 respondents

I think the honesty of the students was helpful. They were honest about their feelings and about what they wanted or needed to help them succeed.

AAPI Male, Teacher, New York

Source: MNP Teacher Survey Data, n820 respondents

Recommendation #2

ACKNOWLEDGE REAL-WORLD CONTEXT: Empathize with students, teachers, and parents* by acknowledging and naming the real-world challenges they face.

Why is this important? Teachers often feel overwhelmed by how often they are asked to adopt new teaching practices and interventions, which can lead to skepticism and make teachers less likely to be receptive to messaging about changing their teaching practice.

*Throughout this website, the research team uses ‘parent’ to refer to both parents and guardians.

IN TEACHERS’ OWN WORDS:

I am experiencing extreme burnout post-COVID. Teachers are definitely feeling the pressure from the state, district, and school administrators for our students to master standardized tests. We (students and teachers) are frustrated, tired, and overwhelmed.

Black Female, Teacher, Texas

Source: MNP Teacher Qualitative Research

Acknowledge the constraints that teachers experience to help reduce their skepticism and make them more open to suggested changes.

Some constraints reported by teachers include include:

- Large class sizes

- Students with different levels of math knowledge and language proficiency in the same classroom

- Gaps in learning from COVID

- Student absences

- Administrative and district pressure and requirements

- Pacing and curriculum requirements

- Emphasis on testing and standardized testing outcomes

- Lack of time both inside and outside the classroom

- Varied level of parental involvement and support at home

- Feeling overwhelmed by the frequent introduction of new pedagogical changes

Sample video message of Black male teacher tested with teacher audience

- The peer messenger acknowledges the pressure of pacing requirements, which helps establish his credibility — he “gets” what teachers have to deal with.

- He also models for other teachers how they may be able to make changes despite challenges they have in and out of the classroom.

He said, ‘I challenged myself to stop saying that I don’t have the time,’ which I feel very inspired by as I’m always stressed on getting everything ready in the short period of time I have.

White Male, Teacher, New York

Source: MNP Teacher Survey Data, n820 respondents

What stands out to me is that even with the pacing guides, curriculum guide and assessment timelines, teachers make it work.

Black Male, Teacher, Florida

Source: MNP Teacher Survey Data, n820 respondents

Recommendation #3

ACKNOWLEDGE EMOTIONS IN MATH LEARNING: Normalize the emotional nature of learning math, and provide examples of how negative emotions can be reinterpreted.

Why is this important? Teachers are sometimes unaware that students’ negative emotions about learning math can interfere with their motivation and willingness to persist. Some teachers may not feel equipped to (or responsible for) helping students manage their negative emotions. Others may feel that the demands of the classroom leave too little time to help students manage their own emotions.

IN TEACHERS’ OWN WORDS:

It is not reasonable to expect teachers to become psychologists in addition to their other duties they must perform…Since I am not a trained counselor, I don’t feel comfortable getting deep emotionally with students.

Hispanic Male, Teacher, California

Source: MNP Teacher Qualitative Research

Encourage teachers to empathize with students’ negative or mixed emotional experiences learning math.

- Utilize prompts that enable teachers to reflect on their own math learning journeys and the emotions they experienced learning math and other subjects as young people themselves.

Use stories of peer teachers to show teachers they have a role in helping students reinterpret their emotions. Stories should:

- Start by affirming teachers’ emotional need to see themselves as good teachers who care for their students while also meeting teachers’ practical need to see positive learning and behavioral outcomes as a result of engaging with students’ emotions.

- Describe how the teacher previously did not recognize how students’ negative emotions were interfering with their math learning.

- Include what prompted the teacher to realize they could help students manage their emotions, including the specific words or phrases they used to reinterpret emotions in the classroom

- Share the change the teacher sees in their students, as a result.

Provide teachers with examples of concrete things they can say to students to help them reinterpret their emotions in real-time. For example, teachers may adapt the following statements:

- When you’re feeling frustrated, confused, or overwhelmed, that’s a signal to ask questions and get extra help.

- When you feel lost in class or don’t understand, it can be embarrassing to ask for help. Those moments are the best time to get extra support. Even though it’s hard, it’s important for you to ask for the help you need.

Teachers can affirm and normalize the emotional nature of learning math – and can help students reframe their emotions as signals to take positive action. Here’s an example of something you could say to a student when they’re feeling stuck, confused, or overwhelmed: ‘When you feel lost in class or don’t understand, it can be embarrassing to ask for help. Those moments are the best time to get extra support. Even though it’s hard, it’s important for you to ask for the help you need.’

Sample print message tested with teacher audience

- This message starts by stating teachers’ role in helping students reframe their own emotions.

- It gives a specific example of something a teacher could say or adapt to their own students.

Recommendation #4

MAKE MATH RELEVANT: Deliver credible and motivational messaging on the relevance, value, and utility of higher-level math (like algebra or above) for students’ lives, desired careers, and futures.

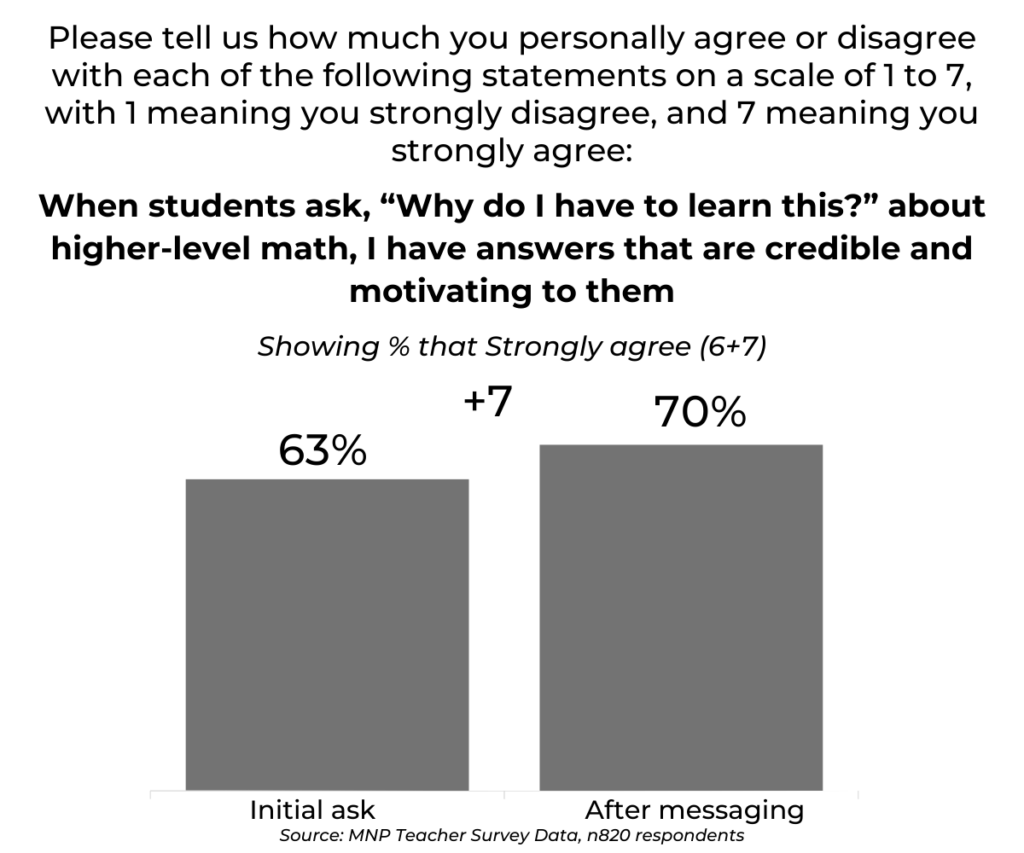

Why is this important? Teachers believe it is important that students understand the relevance of learning higher-level math to their lives. However, many believe higher-level math’s importance is obvious, while others do not feel well-equipped to offer credible examples to different students.

IN TEACHERS’ OWN WORDS:

Relevance and utility would be the one that for me is the one that falls flat. It is the hardest to convey to students and get them to accept and understand. You might reach a few but some are still not there yet with the maturity to be able to grasp why it is important to learn these concepts.

Hispanic Female, Teacher, California

Source: MNP Teacher Qualitative Research

Affirm that teachers get asked frequently about the relevance of math and find it challenging to provide answers that students find credible.

- Provide a range of different examples about the relevance of math so that different students have more opportunities to connect (e.g., the immediate relevance of learning higher-level math may resonate more with middle school students compared to career-oriented examples, though it is helpful to use both).

Frame messages about the relevance of math for students as a “toolbox” for teachers.

- A toolbox reinforces the idea that no single example of relevance will work for all students or for all teachers.

Provide examples about the relevance of math connected to contexts students understand, believe are real, and care about (e.g., keeping your career options open, financial literacy, and having greater financial power so you don’t get scammed or cheated).

- Show how specific math concepts are applied to the real world (e.g., describe how linear equations can help students understand loans).

Examples that are more credible to students help them understand how higher-level math can benefit themselves and their families. Try using examples that:

- Emphasize how knowing higher-level math can help students figure out things that are important to them now, for example, whether it is better to pay for a new phone all at once or in installments and with fees.

- Show how knowing higher-level math can help students protect themselves and their families by making them better able to recognize scams and companies that want to take advantage of them and their families (e.g., predatory lenders and pay-day loans)

- Show how higher-level math can help them ‘pivot’ in their careers. For example, if when they are an adult they find themselves in a job they don’t like, understanding math can help them to have more options about what to do next.

- Higher-level math, like algebra, can help students understand how to manage loans, whether for college, to buy a car, a house, or other big purchases as an adult.

Abstract examples are less likely to be credible for students:

- Math is a universal language

- Math helps you build critical thinking skills

- Messaging that undermines students’ agency (e.g., it’s not fair, but you need to do this or you would graduate/get a good job)

I actually liked some of the answers in the video better than my own…One teacher mentioned adding to each student’s toolbox so they are prepared for whatever life throws at them…I need to add this to my at-the-ready repertoire.

White Female, Teacher, California

Source: MNP Teacher Survey Data, n820 respondents

Recommendation #5

AFFIRM THE VALUE OF MISTAKES: Normalize making mistakes as an important and valuable part of learning, including learning math.

Why is this important? Teachers frequently know that making mistakes can feel demoralizing for students. Some teachers try to keep students motivated by ‘rescuing’ them – giving them the answer rather than working through the mistake with them.

IN STUDENTS’ OWN WORDS:

Show teachers how to respond positively when students make mistakes and address negative emotions such as embarrassment or fear that students often experience when they make mistakes.

- Acknowledge mistakes that students — or adults — make as opportunities for learning.

- Model how you can unpack a mistake to learn from it.

- Affirm that making mistakes does not reflect a student’s overall capability but rather indicates needing more help or support.

- Acknowledge that some mistakes come with higher stakes than others: mistakes in homework or in the classroom can be learning opportunities, whereas mistakes on tests are more consequential. Not acknowledging these differences can undermine the credibility of the messaging.

Help teachers realize that students need to hear explicit messages that reframe making mistakes as a valuable part of the math learning process. You can:

- Share stories from students describing how they feel when they make mistakes and how teachers respond.

- Include negative experiences, such as a student who feels embarrassed or ashamed about mistakes, to help teachers build empathy for students.

- Include positive experiences, such as a student who feels good when a teacher responds non-judgmentally to a mistake by breaking down the specific steps to solving a problem to model for teachers what students need from teachers.

- Share stories from peer teachers describing what they do to create a positive learning environment in their classrooms, including valuing mistakes as learning opportunities. (Utilize diverse teacher messengers with varied levels of teaching experience who can share their own stories and best practices that destigmatize students’ mistakes.)

- The messenger begins by establishing his credibility by citing his experience and then offers a straightforward strategy to normalize mistakes and reaffirm they are part of the learning process (including his own role-modeling of making mistakes which lets students know that mistakes are common and okay).

Based on the last video I watched in which other tenured teachers shared examples of phrases they use with their own students while I teaching, I feel I have…a few more techniques I can use when helping my own students cope when they realize they’ve made mistakes — including admitting that I make mistakes, too.

Hispanic Male, Teacher, Texas

Source: MNP Teacher Survey Data, n820 respondents

I liked the video very much and it has shifted my way of asking and welcoming wrong answers, this will help more kids to participate in the classroom discussions.

Hispanic Female, Teacher, Florida

Source: MNP Teacher Qualitative Research

Recommendation #6

ENCOURAGE HELP-SEEKING: Build student confidence to seek the help they need to learn math and equip parents and teachers with messaging that supports and encourages students to seek out help.

Why is this important? Teachers often expect students to ask questions or seek help when they need it, but many students won’t ask for help unprompted, in part because they feel uncomfortable doing so, or they feel so lost they are unsure of what to even ask.

75% OF TEACHER SURVEY RESPONDENTS AGREE THAT “STUDENTS NEED TO TAKE RESPONSIBILITY FOR ASKING FOR THE HELP THEY NEED IF THEY ARE STRUGGLING IN MATH”

Source: MNP Teacher Survey Data, n820 respondents

Encourage teachers to understand better the barriers to seeking help that many students experience. You can:

- Use student stories or reflection questions to motivate teachers to encourage students to ask questions in the classroom and notice how they may be inadvertently discouraging questions.

- Remind teachers about the realities of students’ developmental age (ex: students don’t want to be perceived as needing help, or they are afraid of being teased by other students who will say they are “dumb” for asking questions)

- Show teachers how their behaviors sometimes inadvertently shame or embarrass students (e.g., describe the impact of teachers who respond to questions by saying, “I just explained that” or “You weren’t paying attention”).

Guide teachers to feel better equipped to encourage students to seek help by using messaging interventions that:

- Share stories of peer teachers who have successfully created classroom environments where students regularly ask for help.

- Point out the sources students can easily access to seek help (e.g., in school, after school, online, one-on-one at the teacher’s desk, etc.)

Motivate teachers to create an environment in which students feel more comfortable asking questions with messaging interventions that:

- Highlight stories of other teachers who started more actively soliciting questions and offering different avenues to ask questions (in group settings and one-on-one), which took shame and embarrassment out of learning.

- Share examples of teachers who affirm questions as a valuable part of the learning process:

- Praise asking questions: “That is a great question.”

- Destigmatize asking questions: “It’s helpful when you ask a question. A lot of other students have the same question.”

As teachers, we always think on our feet. I have gotten really good at explaining things in 3 or 4 different ways because I want to make sure as many of my kids as possible can connect to the content and understand the lesson. But I still need students to speak up and ask questions when they need something explained a different way. It’s hard to know where everyone is at when we only have 50-minute classes and so much material to get through.

Sample print message of a teacher tested with teacher audience

Recently I happened to see a YouTube video of a teacher in Atlanta who does this thing where she praises kids for asking questions. So, for example, when someone asks a question, she tells the student, ‘It’s really courageous of you to speak up. When you speak up you are helping your classmates to learn too.’ I decided to try it with my kids when the new semester started.

Now that I’ve started praising kids for asking questions, even more of my students are asking questions when they are getting stuck or have made a mistake on a problem they are trying to solve. I feel like in my small way, I’m helping kids in my class to feel more confident in the classroom. This will serve them in my class and also in their education to come.

- This messenger begins with empathy for other teachers by acknowledging the challenges teachers face to creating good math learning environments for students.

- They then model a journey of realizing there is something they could do better to encourage student help-seeking behavior and implementing that change. Importantly, the messenger also describes the positive impact of the change — demonstrating to other teachers that it might be effective for them as well.

I love the fact that some math teachers would help in private for shy students because no one wants to be wrong even though we are in school to learn. So I will definitely take inspiration. I always tell my students to message me if they need help but from now on I will make a space where you can come directly for help.

White Male, Teacher, Texas

Source: MNP Teacher Survey Data, n820 respondents

Before I thought there was nothing I could do to help a student who couldn’t ask a question when they needed to, or were too busy/afraid to set up a meeting. I heard from one of the parts of this survey that teachers keep their emails open, and it seems like a much less stressful environment for the students to ask questions

White Female, Teacher, California

Source: MNP Teacher Survey Data, n820 respondents

Recommendation #7

REFRAME STRUGGLE AND CAPABILITY: Reframe struggle from a sign of lacking capability to a sign of needing support.

Why is this important? Teachers’ own beliefs can reinforce the notion that only some students can be good at math or can learn higher-level math.

61% OF TEACHER SURVEY RESPONDENTS SAY THEY AGREE WITH THE STATEMENT

“Some students just don’t seem to get higher-level math, no matter how many different ways it’s taught or explained”

(5-7 on a scale of 1 to 7)

Source: MNP Teacher Survey Data, n820 respondents

Encourage teachers to reflect on when and why they determine that some students are unable or less likely to be able to learn higher-level math, like algebra.

You can:

- Share stories of peer teachers who describe their own motivations to reconsider how they determine students’ capability in the classroom.

- For example, spotlight stories where a teacher shares: when they realized they were assuming specific students could not or would not understand the materials; ignored students who struggle often or don’t appear to get math. Then counter this with what led the teacher to question their own behavior, and how small changes helped them to engage with this student differently in order to get them the help they needed.

- Share messages that describe the challenges of teaching a class with students at different levels of math proficiency and how peer teachers have successfully managed this range in their own classrooms.

- This messenger begins by providing the motivation for reassessing some of her approaches in the classroom — she not only wants her students to learn but also to feel proud of themselves.

- She also describes a common (though problematic) teacher tactic of “rescuing” students, and shows others how to pivot to a different approach in small steps (e.g., it does not require a complete overhaul to their pedagogy).

Recommendation #8

REASSESS ASSUMPTIONS: Encourage teachers to reexamine their assumptions about what certain student behaviors mean and the impact of students’ negative emotions on their math learning experience.

Why is this important? Teachers often feel they do not have the time to provide every student with one-on-one support. When teachers see certain student behaviors — like failing to complete their coursework — they interpret that as a lack of interest in learning. As a result, they focus their attention on other students.

IN TEACHERS’ OWN WORDS:

I don’t like having to take on students that are unwilling to learn, since I can be investing that time with students that are more proactive and receptive.

AAPI Male, Teacher, Florida

Source: MNP Teacher Qualitative Research

Encourage teachers to get curious about how students feel about learning math and the connection between student behaviors and student emotions.

You can:

- Help teachers to explore potential alternative reasons for student behaviors in class by reflecting on questions such as:

- What do I believe confusion and frustration look like in my students?

- Could this student feel lost or stuck on a problem or a concept or frustrated and overwhelmed, so they have given up?

- How can I find out if something else is going on for this student?

Provide opportunities for teachers to reflect on how they interpret certain student behaviors. You can:

- Share stories from students’ perspectives that describe the behaviors they do when they feel stressed or overwhelmed, such as doodling, submitting a blank worksheet or test, or talking to another student in class.

- Encourage teachers to reflect on their own assumptions about what these behaviors (above) represent.

I do my best to help my students learn, and as long as a student is willing to try, I can help them make progress. But last year, a failing student helped me to grow in an unexpected way. Alex was failing my Algebra 1 class and seemed checked out – he never raised his hand, didn’t turn in homework, and I could see him doodling during class instead of taking notes.

Sample print message of a teacher tested with teacher audience

One day I got an email from Alex’s mom that said he had tried to work on his homework in the beginning of the year but felt completely stuck, and she felt like she didn’t understand the math well enough to help him. She said she encouraged Alex to ask questions in class, but he was so confused he didn’t even know what questions to ask.

When I reflected on what she said, I wondered whether I had a blind spot for students like Alex who were failing quietly. I showed Alex and his mom some places to get extra support online, and started meeting with him once a week. Showing that I cared about his learning seemed to make a big difference. He began to raise his hand and turn in homework. He got his grade up to a C by the end of the semester.

This shifted my perspective in a small, but transformative way—the importance of checking my own assumptions about what’s really going on when a student seems checked out.

- The messenger expresses good intentions and a belief that students need to meet the teacher halfway — which is shared by many teachers

- Then they name some behaviors that teachers report commonly seeing, and interpreting as the student being “checked out.”

- After getting more information, the messenger models a change of heart and realization that the student is not intentionally disengaging, but needs extra support.

Recommendation #9

PRIORITIZE BUILDING RELATIONSHIPS: Show teachers the impact of their relationships with students on math learning, and support teachers to prioritize building relationships in their classrooms.

Why is this important? Teachers believe their primary goal is to help students learn math. While teachers often believe building relationships with students is important, they often do not feel they have time to prioritize this.

IN TEACHERS’ OWN WORDS:

[Getting to know all your students] is the ideal, but it is often difficult when you have 150 students to get to know. Some students make it easier to get to know them and look for the connections to their teachers early on, but some want to fly under the radar and would rather be anonymous.

White Female, Teacher, New York

Source: MNP Teacher Qualitative Research

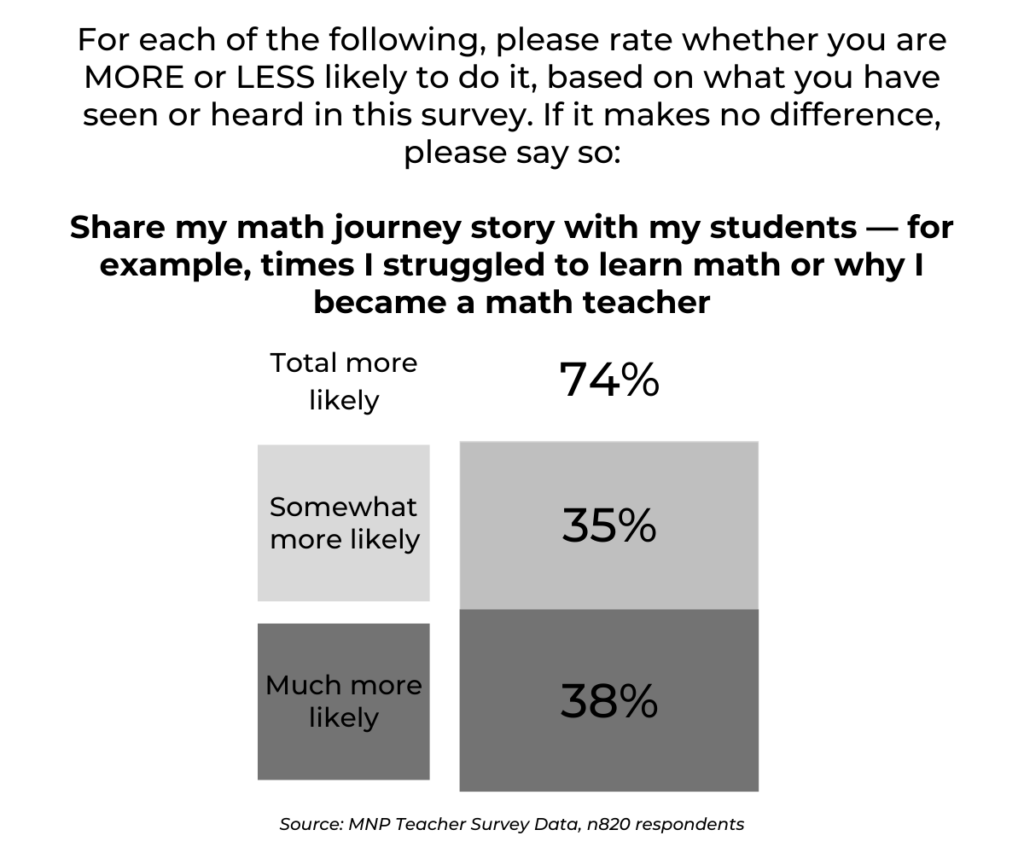

Position building relationships as critical to learning math, an element of math learning that significantly helps students learn higher-level math effectively and successfully.

Leverage teachers’ desire to help their students to motivate and encourage teachers to take on and try out interventions. You can:

- Show the power of small changes teachers can make to build and strengthen relationships with students

- Provide a range of small-scale interventions aimed at teachers and share how these interventions have been successfully adapted by other teachers with minimal preparation and time investment.

Show teachers how developing good relationships with students has a positive impact on their math learning and support teachers to prioritize building relationships with students in their classrooms. You can:

- Tap into the beliefs most teachers have about the importance of belonging and relationships for students’ learning.

- Utilize stories from both students and peer teachers to emphasize the importance of building empathy and trust in the classroom, and how once built, trust yields positive learning outcomes.

- Providing examples that match the varied needs and realities of different types of teachers (e.g., new and seasoned), working with different student demographics, in different geographic and political contexts.

Teachers know they need to build connections with students; however, there is often limited time to connect with each student individually. Teachers can build relationships with students in ways that are meaningful and built on mutual respect by sharing stories with the class about their own math learning experiences, or a story that connects those experiences with the decision to become a math teacher. These types of honest personal stories, which include challenges along the way, help to build trust with students.

Sample print message tested with teacher audience

- The message begins by affirming teachers’ existing beliefs and also the real-life constraints they face which makes it more likely to create an emotional connection and establish credibility with teacher audiences.

- It then offers examples that are easy for teachers to implement and require little, if any, additional time from a class period.