Messaging Recommendations

Audience: Parents

The following messaging recommendations are informed by insights and findings from The Math Narrative Project. They provide guidance on how to effectively communicate with 6th to 10th grade students, parents*, and math teachers. Recommendations include guidance about specific framing, language, and stories that research participants found persuasive. They also provide insight into what types of messengers are best positioned and most effective in delivering a particular message.

The recommendations on this page are intended for people communicating directly with parents. They are meant to support professionals, including teachers, instructional designers, district leaders, curriculum developers, content developers, and others who work to engage, motivate, and enable students to learn math.

*Throughout this website, the research team uses ‘parent’ to refer to both parents and guardians.

Recommendation #1

ELEVATE STUDENT AGENCY: Messaging should elevate student agency and center students’ emotions and experiences, which are critical to their math learning.

Why is this important? When parents see their child struggle with learning math, some say to “just try harder”, while other parents try to minimize the stress children feel. Parents may not realize they can encourage their child to advocate for themselves.

*Throughout this website, the research team uses ‘parent’ to refer to both parents and guardians.

IN PARENTS’ OWN WORDS:

I just want them to be comfortable or just pass by. My expectation is I just want him to learn and know the basics…he’s struggling even with the basics — it bothers him, so I want him to be able to be OK as an adult just for the everyday things. I’m not talking about trigonometry, geometry, any of — algebra not even. Just to be able to be comfortable knowing what he knows.

Hispanic Female, Parent/Guardian, New York

Source: MNP Parent Qualitative Research

Encourage parents to get curious about their child’s math learning experience.

- Equip parents with questions they can ask to get their child to share more about their experiences learning math.

- For example, parents can describe steps they took to get their children to open up about their experiences learning math, and the changes they then took to better support their child’s math learning.

Show parents how children can exercise agency in their math learning.

- Share short stories that center a diversity of choices a student can make to positively impact their learning (e.g., include decisions a student makes every day in math class, asking for and accepting help, seeking or accepting resources, whether to do homework or not, deciding to practice a sport, music, theater, dance, etc.)

“Talk with your child about the value of persistence and the idea that mistakes are learning opportunities.

Acknowledge negative feelings like frustration but also try to surface other more positive feelings, like curiosity in learning, or the feeling of persisting through something hard and eventually succeeding. This can build confidence for children, and encourage them not to give up when facing challenges.

As a parent, you may or may not feel like you personally can help your child with math when they feel stuck or confused.

However, there may be other ways you can support them in learning math:

- Stay engaged and curious. Lean into the emotional side of math and ask how they’re feeling to prevent a self-defeating attitude.

- Ask for help: whether it is asking a teacher for help at lunchtime or after school, or feeling empowered to ask for help in class, remind them it is good to ask for help.”

Sample print message tested with parent audience

- This message lifts up values many parents want to instill in their children, like persistence and learning from mistakes.

- It also gives suggestions about how parents can help their child channel negative emotions into something fruitful, like building confidence and persistence, which can help parents feel better equipped to talk to their child.

- Importantly, it encourages parents to center their child’s agency by tapping into their curiosity for learning and confidence in facing their own challenges.

When parents were asked what they’re thinking about differently:

Begin to have a more open dialogue with your child no matter your attitude or beliefs on math. Having more of an understanding where my daughter is coming from and how I can help her get the right resources.

White Female, Parent/Guardian, Florida

Source: MNP Parent Qualitative Research

This made me realize my own faults and what I can do better to improve myself. If anything, I need to be more patient, and allow my kids to freely express themselves [so I can] understand their struggles…I have to talk to my kids to see how they feel about their math class.

AAPI Male, Parent/Guardian, California

Source: MNP Parent Qualitative Research

Recommendation #2

ACKNOWLEDGE REAL-WORLD CONTEXT: Empathize with students, teachers, and parents by acknowledging and naming the real-world challenges they face.

Why is this important? Parents sometimes feel defensive when presented with messaging that does not acknowledge the obstacles they sometimes face while trying to support their children’s math learning.

IN PARENTS’ OWN WORDS:

An early version of messaging that did not start by affirming parents’ desire to be good parents and just presented advice resulted in this type of negative reaction:

It was more advice than anything about being a parent…which in a way comes across as parent shaming. I think what is missing is being more sensitive to the parents and their needs.

AAPI Female, Parent/Guardian, California

Source: MNP Parent Qualitative Research

Affirm parents’ desire to be a “good parent” implicitly or explicitly. You can:

- Affirm that parents face many challenges, have good intentions, and want to do right by their children.

- Acknowledge that most parents strive to be “good parents,” and want to be able to help their children succeed, including finding resources to support their child when learning math gets hard.

Acknowledge the factors that may influence how parents feel about supporting their child’s math learning, including:

- Parents’ own experience with learning math and perception of their own math capability.

- The shift to Common Core, and how this makes it more difficult for some parents to help their children learn “new math”.

- Adolescent development, and the changes that young people go through physiologically, emotionally, and biologically between 6th and 10th grades.

- Emphasizing the ways parents can support their child’s math learning with other resources, rather than needing to be able to directly help them.

“There’s also a fundamental desire for parents to want to support their children, even when they don’t know how. Today’s math curriculum often looks very different to parents from what they studied growing up. Either it’s presented in a new structure like Common Core standards, or parents have simply forgotten what they’ve learned and … can’t understand what their kids are learning. It can be really stressful for parents and their children alike.”

Sample print message from child psychologist/expert messenger tested with parent audience

- The message begins by acknowledging the desire to be a good parent, which helps calm concerns parents may have about being judged for their actions as a parent.

- Naming some of the common difficulties parents face lets them know they are not alone and can help calm their anxiety about whether or not they are being a “good parent” and are supporting their child’s math learning.

The thing that stands out the most to me is that I am not alone in this…

Black Female, Parent/Guardian, New York

Source: MNP Parent Qualitative Research

To me, the entire [test message] from both sides is very positive. Both sides seem to have a common goal, helping the lady’s daughter. Also, nobody seems to be trying to blame anybody or point fingers in any direction as to the reason that her daughter is in this situation to begin with, so that’s positive as well.

Hispanic Male, Parent/Guardian, Texas

Source: MNP Parent Qualitative Research

Recommendation #3

ACKNOWLEDGE EMOTIONS IN MATH LEARNING: Normalize the emotional nature of learning math, and provide examples of how negative emotions can be reinterpreted.

Why is this important? Parents often have very distinct memories — especially those who had negative experiences — of learning math. Many parents unwittingly pass down negative attitudes about learning math to their children.

IN PARENTS’ OWN WORDS:

Growing up…math would make me cry…It was stressful. But mostly I felt frustrated just thinking about math.

Hispanic Female, Parent/Guardian, California

Source: MNP Parent Qualitative Research

Help parents reduce their stress and manage their own negative emotions about learning math by showing how they can provide support to their child(ren) without passing down their own negative emotions.

- Share stories about parents with varied emotional experiences learning math, showing what a parent can say or do to help their children manage negative emotions related to struggling with math.

- Effective messages show parents how they can unintentionally transmit their stress about learning math to their children by saying things like, “I’m not a math person either” when trying to support their child who is struggling.

Acknowledge negative emotions and affirm struggle as a normal part of children’s math learning process. This can help debunk the notion that some students are naturally good at math and help to reduce parents’ stress about their child’s math learning. You can do this by:

- Offering suggestions for how to speak with their child about their math learning experiences.

- Pairing messages that address or acknowledge students’ negative emotions with messages about higher-level math (like algebra or above) relevance, student capability, and available resources.

- Helping parents reframe student’s negative emotions while also pointing to resources and reassuring parents that children are capable of learning higher-level math. Messages that lack that reassurance or resources can heighten parents’ stress.

“It’s common for adults to proclaim, ‘I’m not a math person.’ But research shows that kids pick up math anxiety from their parents, and it affects kids’ ability to perform in math…instead, do your best to express confidence, calm, and curiosity around math, so that you’re modeling a positive (or at least neutral) attitude toward math for your child.”

Sample print message tested with parent audience

- The message begins by connecting with parents through a common statement some parents make about math.

- After describing a counterproductive behavior, it offers an alternative behavior that may better support a child’s math learning.

- Importantly the message offers an alternative behavior — but does not criticize or judge — the original statement.

I feel that the advice was great and it was helpful, it helped me to monitor what I say about math and make sure it’s not negative…

Black Female, Parent/Guardian, Texas

Source: MNP Parent Qualitative Research

Good reminder to not pass on my negative experiences from high school on to my kids. To make sure I frame those conversations the right way.

White Female, Parent/Guardian, California

Source: MNP Parent Survey Data, n2312 respondents

Recommendation #4

MAKE MATH RELEVANT: Deliver credible and motivational messaging on the relevance, value, and utility of higher-level math for students’ lives, desired careers, and futures.

Why is this important? Parents who don’t use (or don’t realize they use) higher-level math in their everyday lives and work may not feel motivated to expect their children to persist and succeed at learning math. Some parents may also feel they have been able to live a good life without using higher-level math — and therefore tell their children that higher-level math is not important to learn.

IN PARENTS’ OWN WORDS:

Well, higher learning math isn’t useful unless you plan to be in one of them occupations where knowing algebra, geometry or something like calculus may be needed — like being an engineer or an architect. Just my opinion that it wouldn’t be really useful other than that.

White Male, Parent/Guardian, Texas

Source: MNP Parent Qualitative Research

Share credible examples with parents of how higher-level math is relevant for students’ lives, futures, agency, and “adulting.”

Effective examples for parents about the relevance of math connect to contexts that they and their children understand, and believe are real. Examples of relevance may include:

- Learning math helps keep your future career options open.

- Learning math can help prevent you or your family from getting scammed or cheated, and it can help you better understand and choose between loans and interest rates.

Frame higher-level math as opening more career paths to young people rather than being a requirement for a good career (e.g., “higher-level math helps students have more choices about what they do in their lives.”)

Avoid exacerbating parents’ stress around higher-level math by pairing messaging about relevance with messages that:

- Reassure parents all children can get better at math

- Connect parents to different types of resources available to help support their child’s math learning.

Sixty-five percent (65%) of parents in the survey report this is an extremely (31%) or very (34%) credible reason for students to learn higher-level math.

“In the future, you might need to take out a loan to get what you want. This might be to pay for college, or later, to buy a car or a house. In algebra, you learn how compound interest works, and you will need this to understand how much money you need to borrow, and how much interest different banks would charge over different time periods.”

- This example resonates with many parents because it focuses on navigating financial loans — something most adults have had to deal with at some point in their life.

- It also explicitly shows specific ways in which higher-level math (here, algebra) can help you make a good decision.

I just didn’t think of math that way since I never used it as an adult like that, but the survey is right — there could be more and better and new opportunities out there that do require it, so it’s best to just know it.

Hispanic Female, Parent/Guardian, Texas

Source: MNP Parent Survey Data, n2312 respondents

Recommendation #6

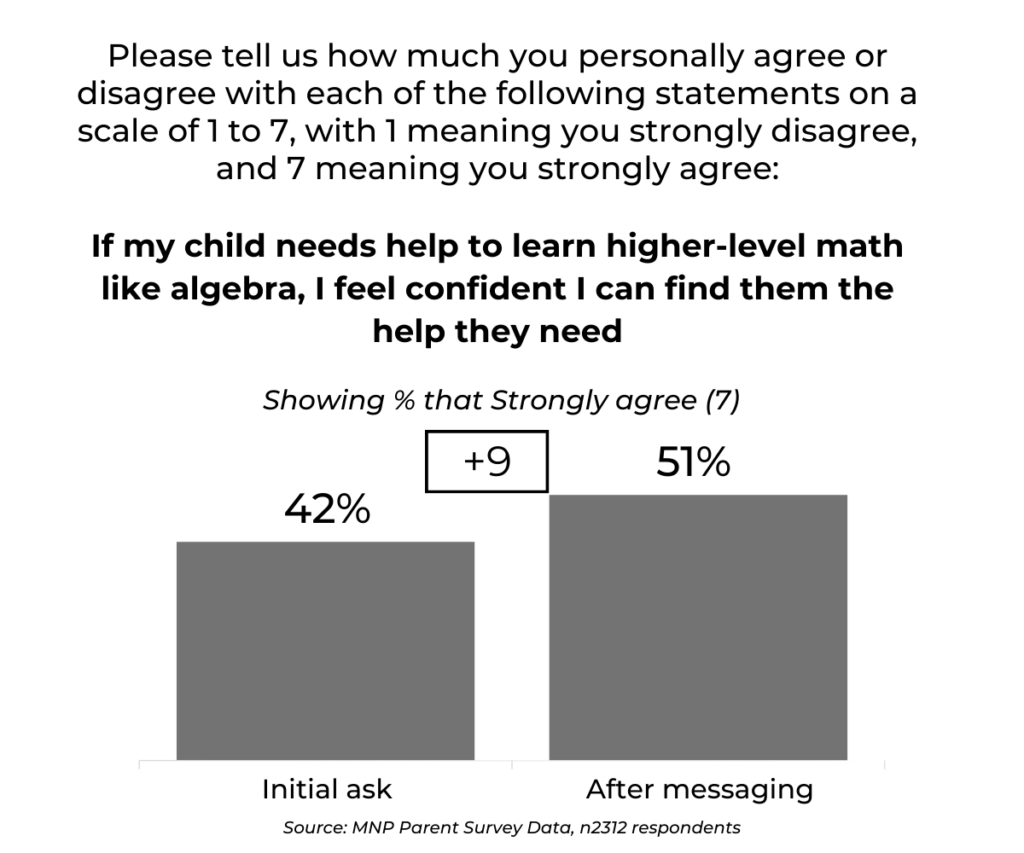

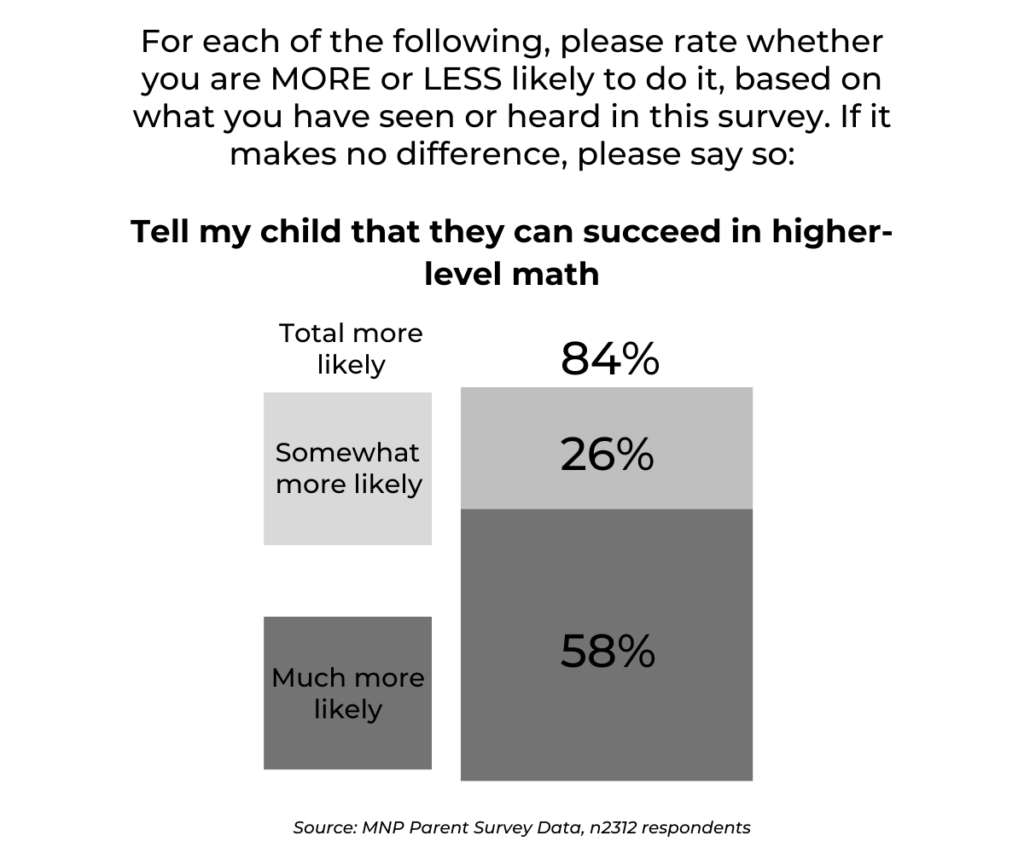

ENCOURAGE HELP-SEEKING: Build student confidence to seek the help they need to learn math and equip parents and teachers with messaging that supports and encourages students to seek out help.

Why is this important? Parents want to help their children with math learning, but often don’t know how to directly help them or where to turn for resources.

IN STUDENTS’ OWN WORDS:

Affirm parents’ desire to be “good parents” who can help their child learn math, even if the help is not direct support for homework.

Build confidence among parents to seek resources and support for their children when learning math feels hard. To do this, you can:

- Normalize the challenges of raising adolescents.

- Ensure messengers are diverse and varied — including parents who have had strong and positive experiences learning math and also those who have not and feel less capable of helping, and regardless found ways to support their child’s math learning.

- Include effective messengers like other parents and education experts who can share their own experiences helping students persist and provide resources.

Provide parents with lists of resources that include a diversity of options with varying levels of financial cost and time commitment.

- Parents also appreciate resources that they can share with their students that don’t depend on the parents’ own math skills.

- Messages for parents that offer resources are more effective when they are packaged and presented with messages that elevate the capability of all students to learn and get better at math.

- Messages about capability give parents hope that encouraging their children to get help and providing resources will actually help rather than cause unnecessary stress.

“You can help your child with math by reassuring them they should look for help or ask for help when they need it, and that if they keep at it with the right help, they will be able to get it.

Here are just some of the different types of support for learning math you can encourage your child to seek out:

- Extra help from their math teacher

- In-school tutoring programs

- Online how-to videos (like on YouTube)

- Free, online tutorial websites (like Khan Academy)”

Sample print message tested with parent audience

- This message begins by affirming parents’ desire to help their child, and lets them know they have a role even if they can’t help directly.

- It then lists a variety of resources — including online and in-person, as well as free and paid options — to show parents the different options that exist since not every resource will work for, or be available to, every child.

I know I may not be great at math but now I know the resources to go to so I can help my child if he is struggling with a math assignment. Before I used to think that because I didn’t know it then I could not be helpful, but just knowing how to look for resources is enough.

AAPI Female, Parent/Guardian, California

Source: MNP Parent Survey Data, n2312 respondents

Recommendation #7

REFRAME STRUGGLE AND CAPABILITY: Reframe struggle from a sign of lacking capability to a sign of needing support.

Why is this important? Parents sometimes believe that children are innately either good at math or they’re not — and that when their children struggle it means that they’re not good at math. They therefore worry that encouraging their child to persist at math will simply cause them more stress without increasing their math ability.

IN PARENTS’ OWN WORDS:

My 8th grader is not so good with math. She requires a lot of time and attention so she is able to fully grasp what she is needing to do. Can be a bit of a ‘problem,’ if you catch my drift.

Black Male, Parent/Guardian, California

Source: MNP Parent Qualitative Research

Motivate parents to encourage their children to persist when learning math gets hard, by elevating three core messages as a package: 1) higher-level math is relevant and valuable, 2) anyone can get better at math with the right support, and 3) effective resources are available.

- Acknowledge and affirm that most parents strive to be “good parents,” including getting their child help when learning math feels difficult.

- Package messages about relevance, capability, and resources together.

- Effective messengers include other parents and education experts who can share their own experiences helping students persist and provide resources.

Tap into parents’ existing beliefs about the value of persistence and apply it to learning higher-level math, using messaging that helps parents:

- Share the idea that mistakes are learning opportunities. Make comparisons to learning other skills or even something like exercise (e.g., “If your muscles are sore or you are short of breath, it just means you’re challenging your body as you strive to get stronger.”)

- Acknowledge negative feelings like frustration, but also try to surface other more positive feelings, like the satisfaction of persisting through something hard and eventually succeeding.

- Encourage children to keep trying. Many children (and adults) feel like if they don’t get math right away, it means they’re not good at math; instead emphasize that what matters isn’t if they “get it” right away, but that they stick with math and ask for help when they need it, so that they learn the math skills that they might need for their futures.

- Remind children that it’s important to find the help that works for them. If they don’t understand the explanations from the teacher or parents, some websites and apps or someone like a peer tutor can walk them through problems and show them different ways to think about math concepts.

- Praise your child’s hard work and effort, rather than praising them for “being smart” or getting things quickly, which can inadvertently discourage them from taking on challenging work and persevering.

Sample video message of AAPI teacher tested with parent audience

- By lifting up a common societal perception of what it means to be good at math, the messenger is connecting with many parents who also have that perception.

- He then pivots — without judgment about that perception — to show parents how there are many different aspects of being good at math, including struggling and working through that struggle.

- Including several different aspects of what it means to be “good at math” increases the likelihood parents and guardians will see some of these aspects in their students.